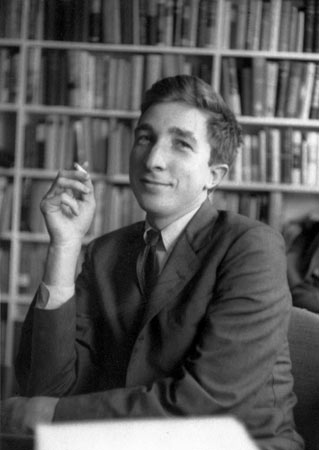

Updike’s Rabbit series is the ripe product of the past century—spanning its entire second half. Much has been said of Updike’s style that renders it justice, albeit in too many words—which is why I am not quoting any of it here. For the uninitiated, suffice it to say that Updike is the unsurpassed master of effaced narration, whose ample resources he exploits fully and to whose strict limits he keeps to the end. The effect on his prose is that of gritty but marvelously eloquent realism. His style is like a counterfeit note indistinguishable from the genuine in that it fabricates a structure as complex and as palpable as that of reality.

It is by a curious twist that in the 20th century, all the while visual art severed its links to physical reality and became more and more abstract, the Western novel reached a degree of naturalism and explicitness unparalleled in the past. Reality began to be captured with increasing, almost manic, precision. Shapes, colors, smells, sounds, textures, moods, minute physical characteristics, even bodily functions—every blade of grass, as it were—would now get cherished in their own right and exposed to the reader.

This recent course taken by Western literature, so much at variance with that on which the rest of Western art has embarked, perhaps owes something to the dawn of cinema: indeed, the camerawork that meticulously shines light on every detail of a staged scene and the characters that inhabit it bears a parallel to the modern literary style, which elucidates accidental details and treats inconsequential actions. But this cannot be the origin of the trend, for even, say, The Age of Innocence, written before the influence of film, already features too much detail and too little plot.

The interest modern intellectual writers take in the middle class, their partiality for ordinary people caught in ordinary moments, and the existentialist currents in which most of them are steeped, they all prejudice against plot and toward excessive detail. Yet none of these sensibilities had taken root in the intellectual and literary circles of Europe and America before World War II.

Perhaps, then, the new style dates as far back as Henry James, who might be called its first prophet, because the effaced narration he so ardently championed cannot lead but to extreme naturalism. And all those other factors—film, culture, philosophy—played auxiliary roles. What does narration, when so thoroughly effaced, do to prose in the long run?

Well, it relieves the narrator of his main responsibility, that of being judicious and selective. The author fears that jumping a few steps in the story for the sake of the plot or exercising his discretion in what to include, what to condense, or what to omit would draw attention to himself as narrator, which is taboo. He thus suppresses his activity within his narration and merely serves as a neutral camera filming the cluttered inner world of his characters and the immense reality outside them, exactly as they would perceive it in real time if they were real people.

Every activity, no matter how trifling, deserves attention now, because to cut out anything from the story would be to assert oneself as narrator. That’s one important reason, besides the extinction of prudishness from modern society, why love-making scenes are now sport in literature and not even the most explicit detail is blinked at. If it happens, then it can and probably should be told. This extreme neutrality is also the enemy of plot, for purposeful action and the clash of opposing wills—the traditional heart and soul of literature—end up diluted among those many tangential actions, hesitations, and observations, to which, because they are commonplace in life, effaced narration feels it must do justice.

In the end, the enterprise of fabricating the most realistic life, world, and set of characters possible is so seductive, so rewarding, and so much in agreement with effaced narration that it becomes an end in itself. Verisimilitude of human existence is the new goal of literature. And the more exhibitionistic a literary style, the better equipped it is to achieve it. When the author conjures up, with uncanny exactitude, specific images in the mind’s eye of the reader—the particular hues mixed in a sunset, the smell of evergreen around a cabin, the texture of a lover’s skin—he is flexing his muscles. Reality gets distilled through the five senses, in surgically precise prose.

Updike does this superbly. He makes you live under Harry Armstrong’s skin. This vicarious experience is the essence of Rabbit. It’s what makes it work. Not surprisingly, it only lasts while you are reading it. When you are done, the aftertaste is mild and fades fast. You remember how good it was, how true to life, how skillful at making you see, hear, and feel, what you should. But in the end, none of what you saw or heard or felt made any lasting impression. The vicarious experience, though uncannily rendered, does not enrich our inner life. In the end, this Harry Angstrom, whom we’ve got to know so intimately, is not worth our acquaintance. Neither is anyone around him. Perfectly as they might be cast, these characters and their interactions signify but very little. And our imagination feels manhandled, used, with nothing to show for the trouble.

After Rabbit, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice or Persuasion will feel like a breath of fresh air. All her novels are written in third-person omniscient. Indeed, no narrator as effaced as the modern novelist could muster that most famous opening sentence in English literature: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” What first struck me in reading Austen after Updike was the sparseness of her descriptions, both of characters and of scenes. It’s the economy of conviction. Masterful at dialogue, Austen nonetheless collapses it into indirect speech when it doesn’t advance the plot or when it is not dramatic. She never indulges in descriptive detail for its own sake. Of Eliza Bennet, we only know that she is of middling height and has dark eyes. Of Mr. Darcy, that he is a tall gentleman, handsome, with a noble air. About the scenes where the plot unfolds we are given very little detail. Permberly is a magnificent estate—a large, stone-built house, furnished tastefully—situated opposite a valley, in the middle of the woods, by a running stream. That’s almost all we are told. But it sticks.

Austen narrates. She is interested in telling a story. Not in providing a voyeuristic peep into the inner life of her characters. Most interesting, I “see” her scenes and characters no less vividly than Updike’s. She sketches the outline and my imagination fills in the rest. In the upshot, the prose is light and nimble. And the reader finds in it room to breathe. His emotional resources are not wasted in attending to minute specifications as to the hair color of Charlotte Lucas or the crookedness of Mr. Collins’s teeth. Austen reminds us that the purpose of a novel is not being John Malkovich, or Rabbit Angstrom. It’s to tell a good story. When authors forget that, they get lost in the weeds. To quote from Elizabeth Bowen’s brilliant essay, “Notes on Writing a Novel”:

Plot is story. It is also “a story” in the nursery sense = lie. The novel lies, in saying that something happened that did not. It must, therefore, contain uncontradictable truth, to warrant the original lie.